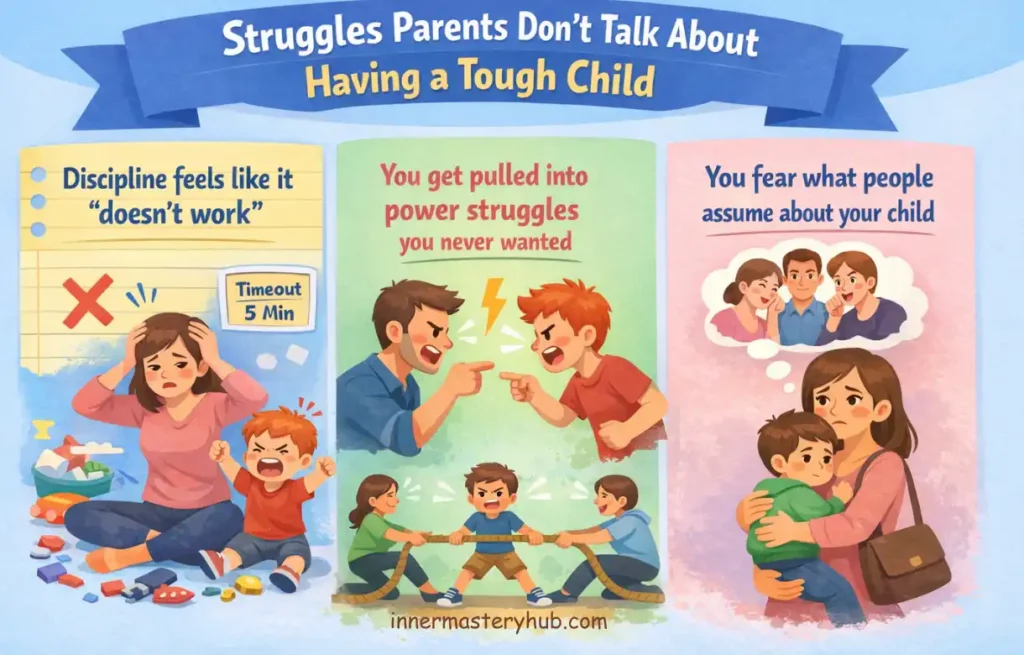

12 Struggles Parents Don’t Talk About Having a Tough Child

If you are having a Tough Child, you already know the hardest part is not only the behaviour. It’s the way the behaviour enters all aspects of your life, including your relationships, your mornings and evenings, and your self-perception. Even though you have a great love for your child, the daily struggles could drag you down. Even if you are a brilliant parent, you may still feel that nothing you do is effective.

Many parents keep quiet out of fear of being criticised. They fear that someone will hear, “I don’t love my child,” if they are honest and say, “I’m not okay today.” But difficulty and love can coexist in the same space.

Tough behaviour is common in childhood, and many kids who struggle also have needs under the surface, stress, anxiety, learning differences, sleep issues, attention problems, or big feelings they cannot manage yet. For example, the U.S. CDC reports that about 11.4% of children ages 3–17 have ever been diagnosed with ADHD, and many have co-occurring conditions. This doesn’t mean your child has ADHD, but it does remind you that intense behaviour is often connected to brain and body factors, not just “bad attitude.”

The hidden weight you carry of having a Tough Child

1) You feel like you are always “on”

Your body learns to stay vigilant at all times and havinhg a tough child is unpredictable also. You wait for the next yell, the next bump, the next argument. Your mind could be looking for danger even when you’re at peace. Your patience is depleted by this continual state of alertness, which makes minor issues feel like big ones.

Stress increases when behaviour is difficult, and high levels of stress might make it more difficult to react kindly. One useful change is to intentionally build small ‘off’ periods into your day, such as a cup of tea before beginning your evening routine, a quick walk after school drop-off or two minutes of calm breathing in nature.

2) You second-guess every decision

You can decide on a rule and move on after a simple day. You wonder whether every decision you make on a bad day may backfire. Should you disregard it? Get it right? Comfort or consequence? Later on, your memory might replay the scene like an unstoppable movie.

Choosing a straightforward “parenting anchor”, such as “I will be calm and firm,” “I will connect first, then correct,” or “I will keep the limit without being cruel”, is one method to help yourself when you’re feeling lost. Put your anchor on paper. After a difficult moment, consider this in one sentence: “Did I return to my anchor?” That one inquiry helps you go back towards stability and away from a never-ending cycle of self-blame.

3) You grieve the parenting story you expected

You might be grieving in private, but many parents don’t express this verbally. You pictured light weekends, hectic but manageable school mornings, and family meals. Rather, you are negotiating every step, including the word “no,” shoes, homework, screens, and bedtime. Even when loss merges with love, it still causes pain.

Comparing your everyday life to your own progress rather than an idealised version is an effective tool for easing grief. “What is one thing that is even 5% better than it was last month?” is a question to ask yourself once a week. Tough behaviour often ends in unequal and poor progress. Appreciating little victories is a decision to let the most difficult times dictate only part of the narrative, not to act as though everything is alright.

4) You feel judged in public

Tantrums in the living room are difficult. It might be devastating to throw a fit at a store. You can hear remarks, see looks, or experience intense discomfort. Your child’s actions may seem to put a spotlight on your parenting at those times.

Having a “public plan” that safeguards your dignity is helpful when dealing with a tough child. This plan should include a rapid escape route, a strategy to keep everyone safe, and a calm phrase you say, such as “I’ve got you, we’re leaving.” Ask yourself, “What did my child need, and what did I need?” later on, when you’re by yourself. That question keeps you in learning Mode rather than shame Mode.

5) You and your partner may not be on the same page

Stress affects adults in different ways. Some become harsh, some humble, and still others shut down. You then quarrel over the fighting. Resentment rises quickly when you carry most of the behavioural burden. In the midst of chaos, a straightforward solution that truly works is not a long talk.

Choose two common rules for the week, and one shared responsibility that you both can handle peacefully during the brief weekly check-in when the house is quiet. Children usually push harder when they perceive parents to be split, and consistency is more important than intensity.

6) You feel isolated from other parents

You may decide to give up playdates. Even though you may grin during school pickup, you may feel that no one truly gets your real life. You lose your perspective and support when you’re alone, which makes everything heavier.

Here’s where you can show a little bravery: pick a safe individual and say one honest statement to them. “This is a difficult season.” “Mornings at our house are really difficult.” You don’t have to tell everyone. All you have to do is break the stillness long enough to remember that you are not alone in this.

7) Screen time becomes the easiest peace… and then causes new battles

Screens may seem to be your only source of relaxation. And to be honest, you need that break occasionally. However, evidence also points to a complex cycle: children who already suffer use screens as a coping mechanism, and increased screen use may worsen emotional and behavioural issues.

Shame isn’t the solution, but building structure is. Set up two clean screen windows and a straightforward off-ramp to avoid arguing all day: “You can choose Lego, music, or drawing when the timer goes off.” Initially, expect a protest. Making people pleased is not your responsibility; your task is to remain stable. “Am I using screens to prevent my child’s feelings?” is a good self-check. You will at times, and that’s alright.

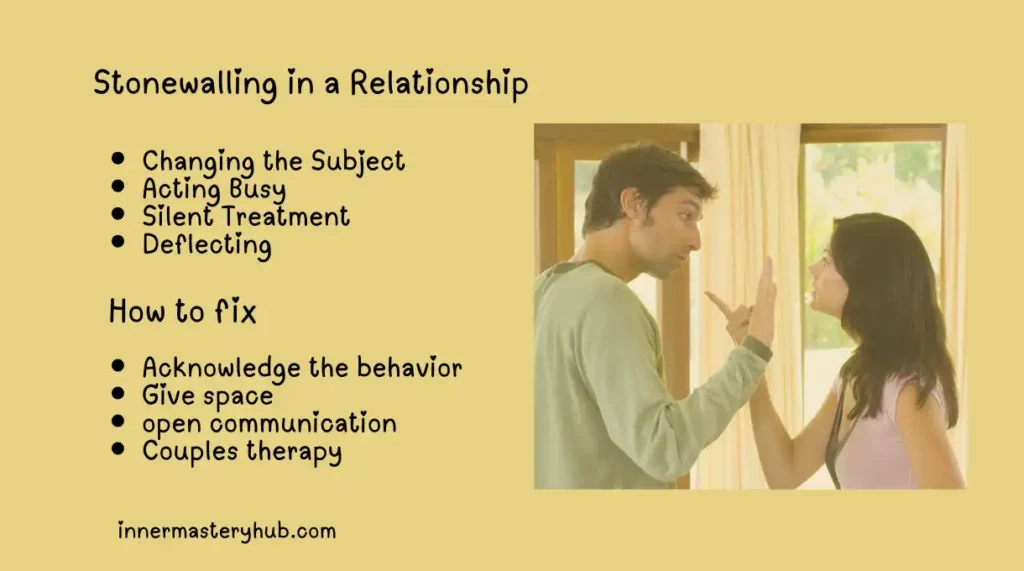

8) Discipline feels like it “doesn’t work”

Punishments seem pointless when dealing with a tough child fights or blows up. You might lose stuff and have more intense outbursts. Try time-outs, and you’ll receive pushback. This is where parent education strategies supported by science might be useful. Parent training programs targeted at disruptive behaviour provide minor to moderate benefits, with smaller effects lasting up to a year, according to a comprehensive analysis.

The lesson is encouraging: abilities count. Try a straightforward three-step discipline pattern: identify the rule, give one option, and calmly follow through. Rebuild the connection thereafter. Limits begin to set in when your youngster understands that you mean what you say and do not reduce their value.

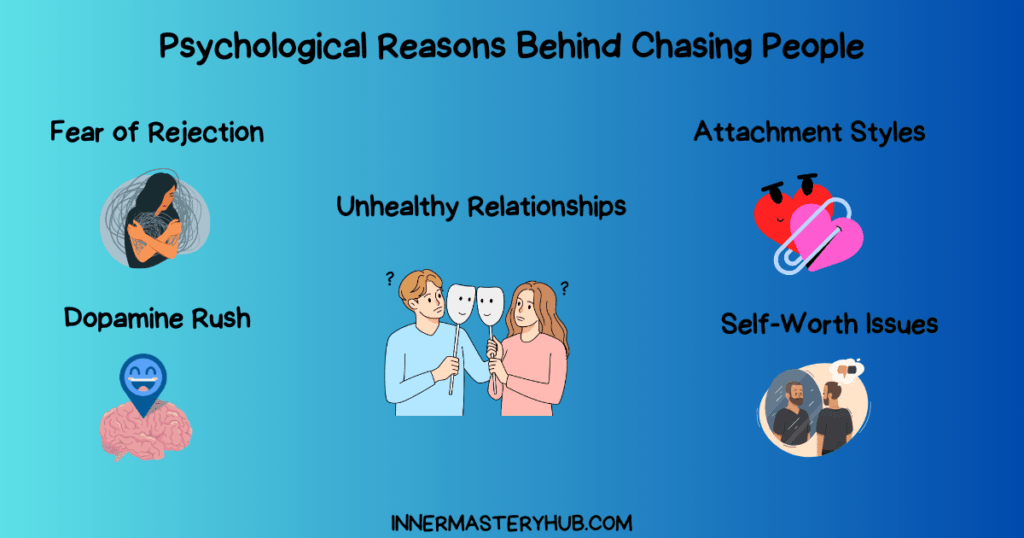

9) You get pulled into power struggles you never wanted

Tough behaviour often starts a debate: you want cooperation, your child wants control, and the dispute takes centre stage. You may feel stuck, as though you had to “win” or risk losing your power. Ending the conflict swiftly while maintaining the limit is a better strategy. Use fewer words, or say one sentence again. Give people a choice only if you genuinely mean it.

Do a brief body check, such as lowering your voice, dropping your shoulders, and unclenching your jaw, if you feel yourself becoming hooked. Your child’s brain reads your body before your reasoning. You add less fuel the calmer you are.

10) You wonder if you should use harsher punishment

Harsher discipline appears appealing when you have no other choice because you want the behaviour to end right away. Strong evidence, however, cautions against the use of physical punishment. Because slapping has been linked to increased aggression and worse behaviour outcomes over time, the American Academy of Paediatrics has warned against it.

You need skill-based management, not fear-based control. If you find yourself thinking, “Nothing else works,” take it as a hint to get help, such as therapy, parent coaching, school meetings, or paediatric check-ins. Stress-relieving tools are what you deserve, not regret-inducing ones.

11) You carry a mental load that nobody sees

You’re not just controlling conduct. To prevent blowups, you are planning around triggers, tracking school notes, and keeping an eye out for warning signals. This unseen labour wears you out. Making some of it accessible and shared is the answer. List the top three “hot spots” of your day, such as bedtime, schoolwork, and mornings.

Next, decide on one minor adjustment for each: get your clothes ready at night, divide your assignments into timed segments, or go to bed fifteen minutes earlier. You’re not attempting to make your life better. Through the most difficult stages, you are creating a more tranquil route.

12) You worry about the future

“Will my child be okay?” is a worry that might keep you up at night. “Are they going to make friends?” “Will they struggle forever?” You might feel scared when you think back to your adolescence. The majority of children’s behaviour is determined throughout time by patterns, skills, and assistance rather than by a single difficult year. The brain of your youngster is still growing.

Your partnership is still developing. Change is also achievable when families learn useful techniques, such as explicit routines, composed follow-through, targeted praise, and dispute resolution. Asking yourself, “What is one skill I can teach this week?” will help you feel more at ease. “What is one skill we practise?” rather than “How do I fix my child?”

What starts to change when you change your approach while having a Tough Child

You may stop living in emergency Mode when you go from reacting to planning. Your child learns what is genuine and what is negotiable when you establish fewer rules and calmly impose them. You provide your child a safer place to land when you choose structure and connection over lectures. Additionally, when you treat your own stress seriously, you safeguard the most important parent your child needs: a stable one who can guide them.

You don’t need to be an ideal parent while dealing with a tough child. You require reproducible parenting, which includes straightforward procedures, unambiguous boundaries, and corrective action when something goes wrong. See a paediatrician or child psychologist if your child exhibits severe behaviour in a variety of contexts, so you can rule out learning difficulties, anxiety, sleep disorders, and attention concerns.

FAQs About Having a Tough Child

Why am I having a Tough Child right now?

Often, it’s stress combined with immature self-control rather than “badness.” When children are exhausted, hungry, overstimulated, irritated, or having difficulty adjusting to change, they will act out. Behaviour becomes the loudest form of communication when learning, attention, anxiety, or sensory needs increase the pressure.

Is it normal dealing with a tough child who is acting defiant?

Defiance is common, particularly during periods of significant expansion. Frequency, intensity, and duration are important. If disobedience occurs regularly, is severe, or occurs both at home and at school, it may indicate more serious issues, and you may require more help and coping mechanisms.

How do I discipline dealing with a tough child without yelling?

Use more follow-through and fewer words. Give a clear decision, state the rule once, and then remain composed. Congratulate whatever little collaboration you observe. If you start to boil, take a 10-second break, speak more quietly, and then go back to the maximum. Your power is calm.

What should I do during a meltdown while dealing with a tough child?

Prioritise safety over education. If your youngster agrees, keep your distance, eliminate any dangers, and speak quietly. Don’t lecture or debate. Once they’ve calmed down, have a quick conversation about what went wrong and what should be done the next time. After the storm has passed, kids learn best.

How can I get my child to listen the first time?

Before correcting, connect. Reach eye level, lightly touch their shoulder, and move in a single, quick direction. Next, wait. Instead of repeating yourself, help them begin the task with you if they ignore you. When you speak clearly and follow through consistently, your listening skills improve.

When should I seek professional help when dealing with a tough child?

If behaviour threatens dealing with a tough child or others, disrupts school, creates a great deal of stress for your family, or does not improve with regular routines, get help. If necessary, a general practitioner or paediatrician can evaluate triggers and refer you.

How do I handle disrespect and rude talk while dealing with a tough child?

Remain uncomplicated and firm. “You can be upset, but you can’t speak to me like that” is an example of setting a limit. If the discussion goes on, stop it. Teach a “retry later” approach: “Try it again with respectful words.” When you continually demand and model respect, it grows.

What to do while dealing with a tough child, when his behaviour is worse in public?

Make a plan in advance and keep things simple. Set expectations before you enter, bring snacks, and limit the length of your outings. Move to a quiet area, repeat one soothing word, and leave if necessary if a meltdown begins. Safety and composure are more important than winning the moment.

Is my child “strong-willed” or is something wrong while having a tough child?

Strong-willed children can still learn boundaries, although they frequently desire control, dispute, and feel strongly. It might be more than temperament if your child also has trouble with sleep, focus, anxiety, learning, or frequent, violent outbursts. An expert examination might provide light on the situation.

How do I cope emotionally when I’m having a Tough Child?

You put less emphasis on perfection and more on fixing. Reset and apologise when you make a mistake. Include brief pauses in your day and seek help as soon as possible. you are not your child’s harsh behaviour. You are also learning.

What does Having a Tough Child mean?

Having a Tough Child means raising a child who is strong-willed, emotionally intense, or resistant to authority. These children often challenge rules, express big emotions, and push boundaries, but they are also passionate, determined, and capable of strong leadership when guided with patience.

How can parents cope with Having a Tough Child?

Parents coping with Having a Tough Child should focus on consistency, calm communication, and clear boundaries. Staying patient, acknowledging emotions, and choosing battles wisely helps reduce conflict. Self-care for parents is also important, as raising a tough child can be emotionally demanding.

Can Having a Tough Child become a strength later in life?

Absolutely. Having a Tough Child often means raising someone with resilience, confidence, and determination. When guided positively, these traits can become strengths like leadership, creativity, and independence. Proper emotional coaching helps tough children channel their intensity into healthy, productive behaviors.